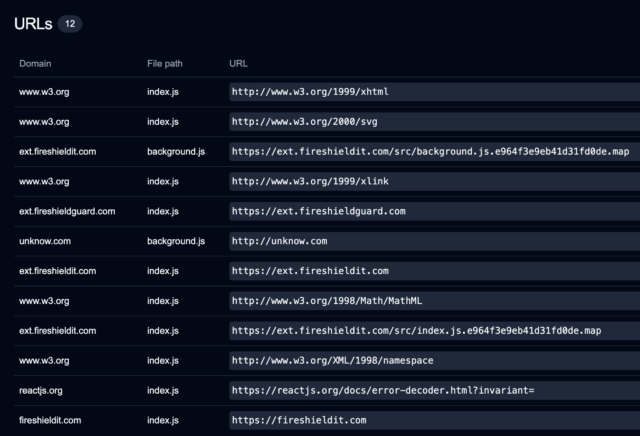

Google is hosting dozens of extensions in its Chrome Web Store that perform suspicious actions on the more than 4 million devices that have installed them and that their developers have taken pains to carefully conceal.

The extensions, which so far number at least 35, use the same code patterns, connect to some of the same servers, and require the same list of sensitive systems permissions, including the ability to interact with web traffic on all URLs visited, access cookies, manage browser tabs, and execute scripts. In more detail, the permissions are:

- Tabs: manage and interact with browser windows

- Cookies: set and access stored browser cookies based on cookie or domain names (ex., "Authorization" or "all cookies for GitHub.com")

- WebRequest: intercept and modify web requests the browser makes

- Storage: ability to store small amounts of information persistently in the browser (these extensions store their command & control configuration here)

- Scripting: the ability to inject new JavaScript into webpages and manipulate the DOM

- Alarms: an internal messaging service to trigger events. The extension uses this to trigger events like a cron job, as it can allow for scheduling the heartbeat callbacks by the extension

:: This works in tandem with other permissions like webRequest, but allows for the extension to functionally interact with all browsing activity (completely unnecessary for an extension that should just look at your installed extensions)

These sorts of permissions give extensions the ability to do all sorts of potentially abusive things and, as such, should be judiciously granted only to trusted extensions that can’t perform core functions without them.

Dubious or suspicious

“At this point, this information should be enough for any organization to reasonably kick this out of their environment as it presents unnecessary risk,” John Tuckner, founder of browser extension analysis firm Secure Annex and the researcher who stumbled on the cluster of extensions, wrote in a post published Thursday. In an email, he said the only permission required for some extensions is management. “Some of the other extensions like the 'Browse Securey' might traditionally require more permissions like 'webRequest' to block malicious sites, but things like access to 'cookies' are definitely not needed across the full list,” he said.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...